Emmanuel Mellet et al in Royal Society Open Science

Publication :

Mellet E, Salagnon M, Majkic A, Cremona S, Joliot M, Jobard G, Mazoyer B, Tzourio-Mazoyer N, d’Errico F. 2019 Neuroimaging supports the representational nature of the earliest human engravings. Royal Society Open Science.6: 90086. http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/lookup/doi/10.1098/rsos.190086

Abtract

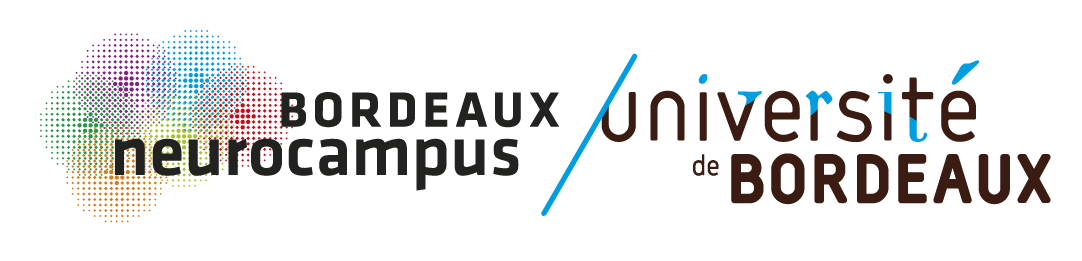

The earliest human graphic productions, consisting of abstract patterns engraved on a variety of media, date to the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic. They are associated with anatomically modern and archaic hominins. The nature and significance of these engravings are still under question. To address this issue, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging to compare brain activations triggered by the perception of engraved patterns dating between 540 000 and 30 000 years before the present with those elicited by the perception of scenes, objects, symbol-like characters and written words. The perception of the engravings bilaterally activated regions along the ventral route in a pattern similar to that activated by the perception of objects, suggesting that these graphic productions are processed as organized visual representations in the brain. Moreover, the perception of the engravings led to a leftward activation of the visual word form area. These results support the hypothesis that these engravings have the visual properties of meaningful representations in present-day humans, and could have served such purpose in early modern humans and archaic hominins.

Comment in french

Bien avant les peintures de la grotte de Lascaux, les premiers humains ont inscrit des motifs abstraits sur des pierres, des coquillages ou des coquilles d’œufs, les plus anciens datant de 540 000 ans. Pour les archéologues qui ont découvert ces tracés préhistoriques la question est de savoir s’ils étaient le fruit du hasard, d’une volonté d’imiter la nature ou dotés d’une signification.

Une collaboration inédite entre des archéologues (du laboratoire PACEA : CNRS / Université de Bordeaux / Ministère de la culture) et des chercheurs en neuroimagerie cognitive de l’IMN (CNRS / université de Bordeaux / CEA) offre pour la première fois des éléments de réponse à cette question. Ces motifs abstraits préhistoriques sont analysés par les mêmes zones du cerveau que celles qui reconnaissent les objets. Ils activent également une région de l’hémisphère gauche bien connue dans le traitement du langage écrit. Les résultats de cette collaboration interdisciplinaire renforcent l’hypothèse que nos ancêtres ont très tôt attribué une signification à leurs tracés, peut-être même symbolique. Ils sont publiés dans Royal Society Open Science le 3 juillet 2019.

A propos : voir la vidéo de l’équipe du GIN tournée l’an dernier

Last update 04/07/19